Well Written - Part V

Regular readers of SWS will know that I’ve got a soft spot for Dhows. And perhaps the most authentic book written in English about voyaging in Dhows was penned by a boy from Melbourne. Although Alan Villiers left school (in Essendon) early, both his writing and his photography show a sensitivity not normally associated with maritime writing in first half of the 20th Century.

He visited Arabia in 1938 because he was certain that he was living through the last days of sail, and was determined to record as much of them as he was able. At Aden, Villiers found an Arab dhow master prepared to take on a lone Westerner as a crewman. Ali bin Nasr el-Nejdi and his Kuwaiti crew were making the age-old voyage from the Gulf to East Africa, coasting on the north-east monsoon winds, with a cargo of dates from Basra. The return voyage would be made in the early summer of 1939, on the first breezes of the south-west monsoon, from East Africa to Kuwait. From this voyage, Villiers fashioned Sons of Sindbad. In a real sense the Thesiger of the Arabian Sea, Villiers voyaged with his companions as an equal, while deferring to their toughness and fortitude, and to their superior knowledge of their trade.

In this passage, more about the passengers and crew than the sailing, Villiers evokes the smells, light and emotions of life on a dhow and tells of the heart wrenching death of one of the female passengers.

The Triumph of Righteousness, photo by Alan Villiers

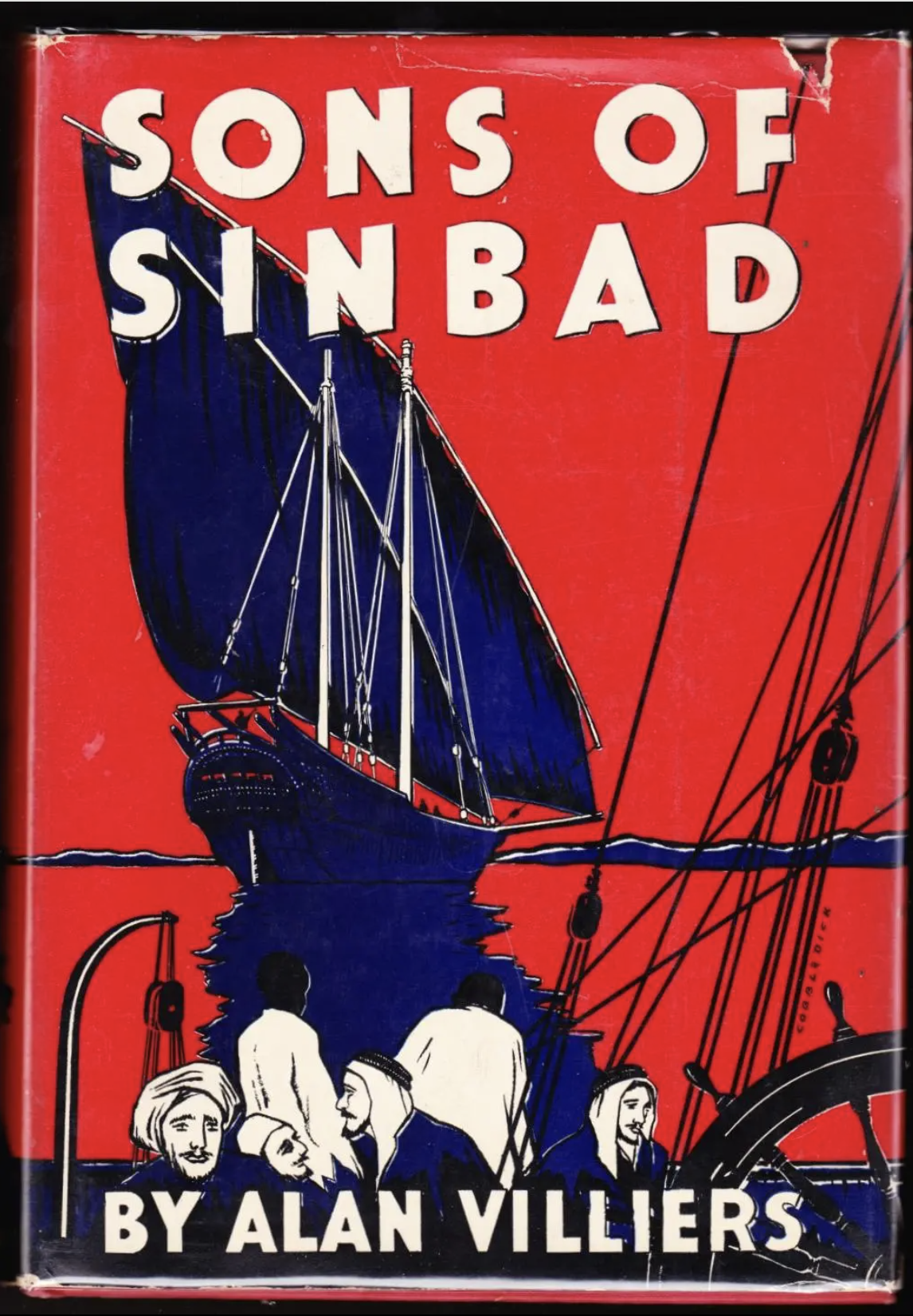

THE SONS OF SINBAD by Alan Villiers

When we had been ten days at Haifun it was announced that we should sail on the morrow. When we had been there twenty days, I was listening to the same announcement with less and less interest. We had watered the ship—I didn’t see why we hadn’t just filled our tanks from the sea, for Haifun water was so salty that I could not drink it—we sold a boat for a hundred rupees to some Somali fishermen; we tried to sell the bad dates from Aden, and failed, because the port medical officer, an Italian, would not allow them to be landed: and we exchanged a little of our rice and sugar for some very high dried fish. This was the sum total of our proceedings at Haifun, so far as the regular business of the ship was concerned. Beyond these things, and all the hashish and haberdashery and whatever else our Sinbads smuggled, we left nothing behind us at Haifun.

Nothing, that is, but the body of a girl who died in the great cabin. She was a young girl, aged perhaps fifteen, but by Arab standards she was a woman and she was going to Zanzibar to be married. One morning Yusuf Shirazi came quietly over to me where I sat on the poop watching a small boat come in from Batina, and said in Arabic, “Come, O Nazarene; a woman has died.” He said it so calmly that for the moment I did not grasp the message: what, a woman dead? From what, and how? But Yusuf did not know. It was a young woman, he said: she died. That was all he knew. She was in the great cabin now. Would I come? The faith of the Arabs in my inconsiderable medical knowledge, merely because a few clean dressings I had put on some wounds did good, was pathetic. Here was death and they thought somehow I could cope with it.

Nejdi was ashore. So were Hamed bin Salim, and Abdulla Nejdi, Said, Majid, and the Seyyid from Mukalla. I asked Yusuf if he was sure the girl was dead. He answered that he was, in a manner that permitted no doubt. Then there was nothing I could do about it. When I heard of death and serious illness aboard that dhow I always feared for epidemics and grave infections, for the conditions were such that had any bad illness come the prospect for all of us would have been serious. Yusuf said the girl had not been sick: she just died. How? I asked him: did someone kill her? He did not know. She had taken a little khubz and some sweetened tea, and then fell back and died. She had not said anything. He was there at the time. He had not noticed, for he was doing some work and paying no attention to the women. One of the older women saw the girl fall back, and then they saw that she had died.

I told him to send a boat ashore for the doctor and Nejdi, for I would not go down until Nejdi came. If the girl was dead I could do nothing. Even if she had been seriously ill, I could have done nothing. But I would have tried. No one else was ill, according to Yusuf. All the occupants of the great cabin had been healthy enough, until then.

After about an hour, Nejdi came with a Somali medical dresser, and we went down. The news had been kept quiet, though somehow the report of death had spread and, for once, conditions were fairly peaceful on board.

In the great cabin the scene was unforgettable. I had not been there since the women had come aboard: no man had, except Yusuf. They had now been cooped up there about a month. The place had been cleared a little, and the stores and ship’s gear moved to the sides, well aft: the bulkhead across the fore part was firmly secured. It was so gloomy that even with the hatch open, it was impossible to see when we first came in from outside, for the hatch was very small and gave little light. Through the small open port on the starboard side one ray of sunlight came, losing itself rapidly among a pile of blocks, and tackles, and empty ghee jars, piled in that corner. After a moment or so, I could see. I saw the women grouped about. There must have been twelve or more, sitting bundled up in black on mats and Beduin rugs. Only their eyes showed, and their eyes watched us. I felt all those eyes on me. In that dull gloom I did not at first see the place where the dead girl was. Then I saw that she was in the center, lying on the floor. Her face was uncovered, now that she was dead. I looked at it and saw, to my surprise, that she had been lovely. It was a startling face to come upon in a place where I had not imagined anything lovely to be. Though I had been with the Arabs for some time, this was the first time I had seen the face of a marriageable young girl. I had not known they could be so lovely.

The ship swung to her moorings, and the light from the port, diffused and golden, swung across the gloom, reaching to the girl. Poor child, even in life she had never belonged down there in that dreadful place, among that crowd of older women who huddled from her, suspicious, almost animal-like, watching not her but us. She should never have been in that frightful travelling prison, delivering her to a harem in Zanzibar, to a husband she had never seen, in an island far from her home. Her skin was like ivory, her features delicate, her little profile gentle and very lovely. Her small mouth was firm and well formed. Her black hair was rich and beautiful, and her eyes were closed as if in sleep. Her dress was of black satin decorated with hand-sewn wire of gold, for some one had put her in her bridal gown. Her small hands lay folded on the half-formed breasts, which were small and delicately rounded. The light moved from her and left the place in which she lay under a dark pall of gloom, but I found myself unable to take my eyes from that dead face. The other women huddled there, silent. One old woman, veiled with the Beduin eye-slitted mask instead of the all-covering veil of the town harem, moved closer, stared at the Somali dresser, and stared at me.

“From what did she die?” she said.

Merely from being there, I should have thought: Such loveliness could not survive that fetid, frightful gloom. Yet they said she had been happy. Accustomed always to hardship—she was from inland, near the desert’s edge—she had not found the great cabin so bad as it seemed to me, but she must have missed fresh air. The fact that she was going far from her home to marry a man she had never seen had not troubled her, for that is a woman’s lot in Arabia. The stench of the place was nauseating—the fumes of the bad ghee and all the other mysterious things of the ship’s stores, the ship’s own aroma of foul bilgewater and fish-oil, the unpleasant odor of the cramped-up human beings. It was as much as I could do to stay down there at all, with the hatch open and the two ports, and the ship quietly moored at anchorage. Yet here this poor girl-child had lived a month. No wonder she was dead: I do not see how she could have stayed alive.

The Somali could assign no cause for death other than heart failure.

“All hearts fail at death,” Nejdi said: “do you know no more than that?”

But the Somali did not. Neither did I.

In the presence of the dead girl Nejdi seemed awed a little, and he swept a look of scorn at the other women. I discovered later that he suspected one of them of having poisoned her, for there was a woman there from the same harem, a woman sent from Zanzibar to collect this pretty virgin. Perhaps an older woman little cares to see fresh loveliness come to her lord’s harem. It was all fantastic to me, like so much of what went on in that dhow. Nejdi was relieved that it was not smallpox or anything like that: a simple case of heart failure was straightforward enough. It was not his business to find out what had caused it.

In the late afternoon they buried her, taking her ashore in the stern-sheets of the longboat. Nejdi had gone then. Hamed bin Salim had charge of the boat and, even in that funeral procession, he still smuggled. He was not the only one who put a few extra money-belts and sarongs about his waist and knees before he went down into the boat, for Said, Majid, and the others were also there, and the boy Mohamed, not grinning now, sat in a new gown and turban up in the bow. The slight small body was covered with a black veil and wrapped in a date-frond mat. It lay in the stern-sheets in the midst of life, for the boat was crowded, and with the Beduin singing quietly and the sailors pulling at the oars, the boat was gone. I did not go to the funeral. These were Muslims and this was their ceremony. But I was sorry for the poor girl, and wondered long about her.

The following day she was apparently forgotten. In the next port I heard Nejdi deny that there had been any deaths on board.

You can read the full text of “Sons of Sinbad” free online HERE