Well Written - Part One

There’s many a page of predictable drivel written by brave adventurers, who probably over estimated their literary talent, while modestly underestimating their sailing skills. But occasionally we stumble across a gem of a chapter that seems to sum up one particular aspect of voyaging better than any photograph or painting. With this in mind we thought we would begin a semi-regularly series featuring some of our favourite sailing prose, deserving of better recognition!

HURRICANE'S WAKE. Around the World in a Ketch - By Ray Kauffman

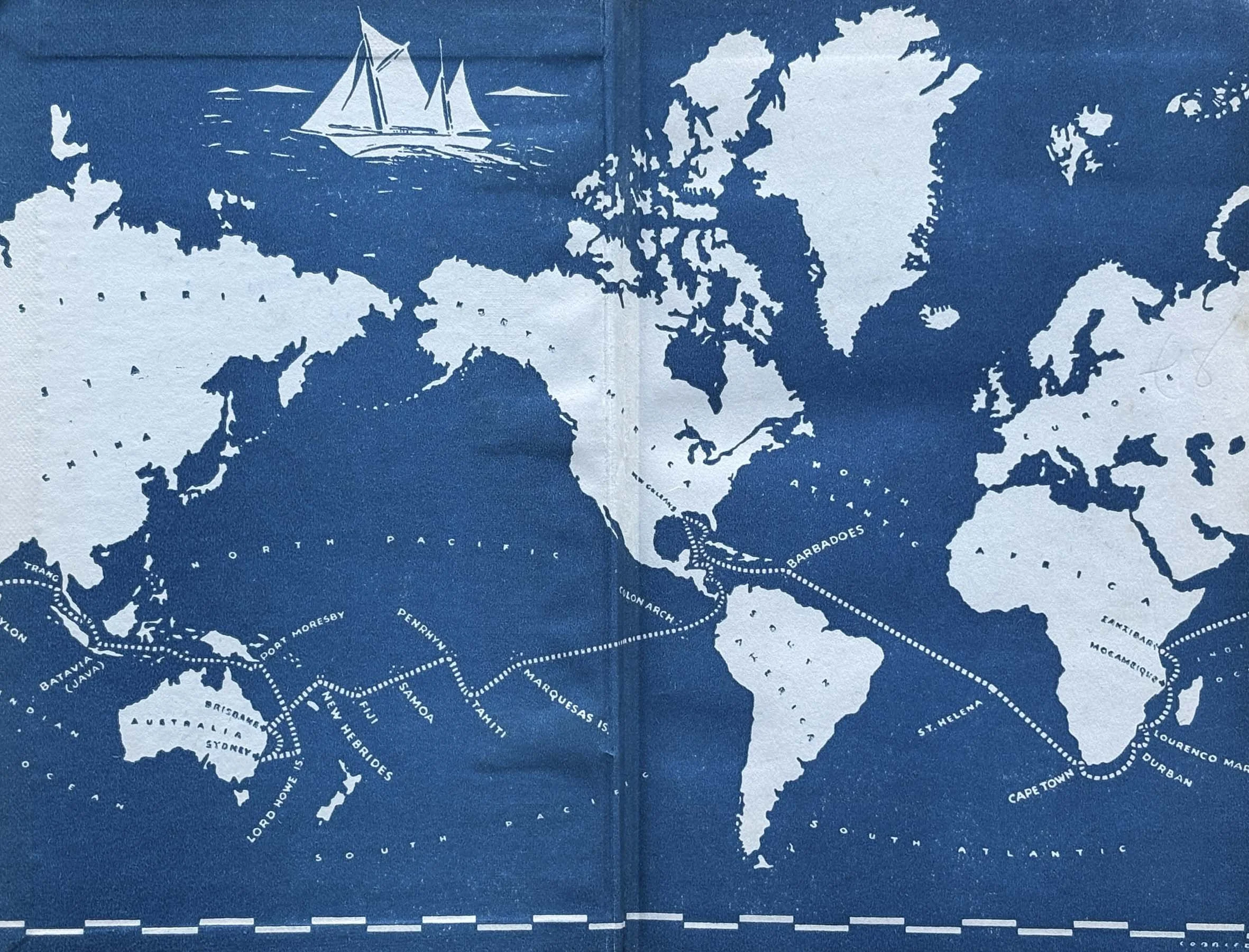

We’ll start the series with Chapter XI from Hurricane's Wake: It’s not a volume you see often in the second hand book stores as it was only published for a few years beginning in 1940. But it is available today digitally HERE The book chronicles a remarkable three-year circumnavigation beginning in 1935 aboard a 45ft ketch named HURRICANE. Kauffman, accompanied by his friend Gerry Mefferd and their Mexican chef/crewman, Hector, set sail from New Orleans, taking what nowadays would be considered the standard tradewinds cruising circumnavigating route. The writing offers the reader an immersive experience of life aboard a small yacht during the pre-World War II era, as exemplified in this lovely chapter written about a windless Pacific passage from Bora Bora to Penrhyn atoll. (The DIRECTOR was a vessel they arranged to sail in company with on the passage)

CHAPTER XI

There was no wind. Hector, sluicing down the hot decks with buckets of sea water, muttered, “Absolutamente no y viento,” and ducked as the main boom swung inboard. Bob squinting at the sky remarked, with the assurance of an old sea dog, “It’s a—— flat calm,” and profanely gave me a hand getting in the slatting mainsail. Gerry was out on the bowsprit furling the jib and trailing his feet in the lumps of slick blue water that rolled and pitched the ship. The mizzen and staysail were left on, sheeted in flat to help steady her, but the heavy canvas slatted and the reef points whipping against the sail sounded like rain on a roof. The iron shackle on the sheet block banging on the traveller was silenced by a lashing with a rope end.

Wet with perspiration, we lay on the deck-house with the awning between us and the blazing sun, our skin chafing on the paintwork with every roll of the ship, dispiritedly watching a wisp of black smoke following the two bare poles on the DIRECTOR scarcely three miles to the westward, and speculating on how many hours we would have beaten our rivals if the wind had held. Aboard were only five gallons of emergency gasoline, while the Director, with a drum of fuel oil, was maintaining a schedule. Gerry said that he was now convinced that the most valuable sail on a boat was the diesel.

The first day out of Bora Bora in a moderate breeze we had bowled along at six and a half knots under all sail and by dark the DIRECTOR was hull down astern. But in the morning our exuberance had died with the wind until we lay writhing on the uneven surface of a glassy sea like a drunken porpoise. Our destination, the atoll of Penrhyn, eight degrees south of the Line, was five hundred miles north-west; Borabora was only a hundred and thirty miles astern, and I thought of the farewell feast when Marii had killed a pig and roasted it whole on the hot stones of his native oven. It had been a gala event. The DIRECTOR arriving

from Papeete on April first with a good cargo of Tahitian rum, bought in bond at a ridiculously low price, had generously contributed to the hilarity of the occasion. The huge dinner had been served in front of Marii’s fare on a long low table decorated with flowers, with banana leaves for plates.

Sadly I remembered the last night ashore when our girls had cried softly, gazing seaward into the starry night. Practical Bob had consoled us with the thought that, with Tahitian women, out of sight was out of mind and that, as soon as the HURRICANE was hull down to the westward, tears would dry and we would be forgotten. But I wondered about Marii and visioned again his face, with tears silently streaming over the smooth brown skin as he stood motionless on the end of the jetty. In the background, the village, with its widespread flamboyant and hibiscus-lined road, the huge breadfruit and mango trees and the tall palms that leaned over the wind-darkened lagoon, had sparkled in the late morning sun. I had looked aloft to gauge the direction of the wind outside and saw the white puffed clouds of a trade-wind sky drifting across the naked face of the mountain. Waving good-bye we had cast off the lines and sailed out of the pass just ahead of the DIRECTOR’s bowsprit, entering once more the world of water and sky. Before dark the twin peaks of Bora Bora had dropped below the horizon and, with the island gone forever, life was limited again within the ship.

The sun settling in the sea, without a cloud to paint, momentarily reddened the tops of the swells. Optimistically, I kept regular watches all night, with instructions to call me when the wind came back. In the heart of the trade wind belt with the southern winter coming on, calms were rare and of short duration, according to the wind chart and pilot book. But in the morning the sun came out of the sea into the same blank sky and in two hours the heat was intense, with not a breath of air stirring for relief. The lumps of blue were ironed out and we lay quietly, the canvas scarcely fluttering with the gentle roll of an almost imperceptible swell. Under the awning we closed our eyes to keep out the reflected light from the glassy water and patiently prayed for the night. To-morrow, always to-morrow, the wind would come.

For eight days the HURRICANE lay becalmed with only an occasional cat’s-paw to fill the sails and shorten the distance to Penrhyn by a few miles. I no longer kept watches but hung a white light in the rigging and all hands slept on deck, still as death, through the cool windless night. During the long hot day Gerry pounded the typewriter on deck, bringing his correspondence up to date and beyond, thought up new ways to serve canned foods, splashed buckets of sea water over himself or crawled aloft in desperation, scanning the horizon for a ship or even a bit of driftwood, anything to vary that dead oily heat-reflecting ocean under that white hot sky. Bob slept most of the time or regaled us with stories of his adventures ashore in various seaports throughout the world. Hector thrived on calms when the ship made so little work, and amused himself drawing pictures with coloured crayon. With an Indian’s love for colour, he laid it on thick, and on Easter Sunday he drew a lurid picture representing the resurrection of Christ and tacked it up in the galley. And a light breeze came out of the north-east, sending us thirty-five miles on our way during the next twenty hours. Bob had stuck his knife in a check in the mainmast, and Gerry and I whistled for wind, but Hector, successful, said, “Capitan, I breeng zee wind.”

But it died again and the heat hung under the awning and the decks were too hot to touch. We read as much as our eyes could stand, counting the hours until the sun would set. With a lookout for sharks, we often swam over the side and looked at the red copper paint on the bottom of the ship, trailing a line from the chain plates to help us back aboard. Once, Gerry and I, from sheer boredom, launched the skiff and rowed around and around the ship, watching the reflections curve over the glassy swell.

On the morning of the ninth day, a bank of clouds spreading over the horizon ahead of the sun withheld the heat and promised wind. Gerry and I scrambled up the rigging to the crosstrees and looked anxiously eastward. The water under the line of clouds was dark.

“Is that wind or shadow?” Gerry asked.

“It must be wind because the low clouds are moving fast,” I answered.

“Look, Coppy,” said Gerry, excitedly pointing astern. “Wind for sure.”

Turning, I saw little patches of ripples, darkening the water, spread slowly across the sea until the calm shiny areas were reduced to irregular strips on the new pattern of ruffled surface; then a faint breeze whispered in my ear and a breath of cool air caressed my naked back.

“Take in the awning,” I shouted joyously down to Bob; and swinging on to the main halyard, slid to the deck where the breeze stirring aloft was not yet felt. Life aboard exhilarated. Gerry was doing acrobatics descending the main rigging. Bob, with his credulous blue eyes wide open, and grinning from ear to ear for the first time in several days, worked furiously to clear the decks. Mattresses and pillows were tossed down the companionway. So long had we been inert that I sent Hector below to look after the galley and see that everything was stowed for sea. The cloud bank was approaching the zenith and the line of dark water was visible from the deck. The mizzen and staysail filled, gently moving the ship. I jumped to the helm and the ship swung slowly around on the course. Little swirls and bubbles trailed off the keel. Hilariously we shouted and sang as the mainsail unfolded and fluttered aloft with the clicking of patent blocks. The slack sheets slowly straightened and the booms, lifting slightly, swung outboard. The jib was set and the bow, slicing the little lagoon-like waves, sounded like a spring trickling over small stones. We heeled to the freshening breeze and the water boiled under the counter.

The line of clouds was overhead and the wind sang through the rigging, whipping the pareus around our knees. We raced along in water still smooth. The sky to leeward was bright with sunshine, reminding us of the dead but hot world we had left. To windward great curtains of rain obliqued down to the sea. The wind in the rigging increased to a steady hum and a column of water shot through the lee scuppers. Down, down we went until the lee rail was smothered in white water. I felt as if we were flying and looked aloft at the dark clouds racing over the grey sky. The sheets were tight as violin strings. The sea was building up, but so hard was the HURRICANE driving that she lay over deep in water, steady as a boat careening on a beach. The wind increased, shrieking in the rigging; then the squall burst and the rain thundered on deck, darkened the white sails and sun-bleached lines, and beat the whitecaps from the sea.

“Soap, soap,” I cried, and Hector dived below, coming up stark naked with several bars of soap. All hands stripped and scrubbed in the driving rain until the scuppers ran suds. Taking turns on the helm, we washed our hair, our pareus and bed sheets as fast as possible, fearful lest the rain squall would blow over and leave us lathered in soap-suds. After the intense heat, the rain was icy cold and we shivered, our skin covered with goose-flesh. In half an hour the wind eased up a little and a long line of light sky showed to windward. To leeward a great rainbow arched across the sky against the black background of the departing squall. Frantically, we washed off the soap with the last of the rain.

The sun beat down again but its warmth was welcome. The wind held and the water was alive again, sparkling all blue and white. Little puffy clouds floating across the sun cast purple shadows on the sea as they followed the squall to the westward. Our clothes, hung up to dry, flew gaily from the rigging. All hands were eager to take their watch and feel the ship tug at the helm. The calm was forgotten. Soon now, we could look for the tops of the coconuts surrounding Penrhyn’s pearl lagoon.

For those wanting to know more about Kauffman's life and voyages, the Gerald W. Mefferd Papers at Mystic Seaport Museum contain diaries, letters, and a biographical sketch of Kauffman, offering a deeper look into their shared journey and friendship. Or there’s this wonderful video from 1938 of them arriving home.

And if you have any suggestions for great and under-rated sailing prose that needs to be shared then LET US KNOW